U1.02 — Australian Consumer Law: Misleading & Deceptive Conduct in Marketing

Overview

Dotpoint 2: Australian consumer law in relation to misleading and deceptive conduct in business marketing activity

Australian Consumer Law (ACL) is the set of rules that ensures businesses treat customers fairly and that products and services do what they are supposed to do.

It applies Australia-wide to all businesses and is enforced by the ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission).

One important function of the ACL is to prevent misleading and deceptive conduct in business marketing activity.

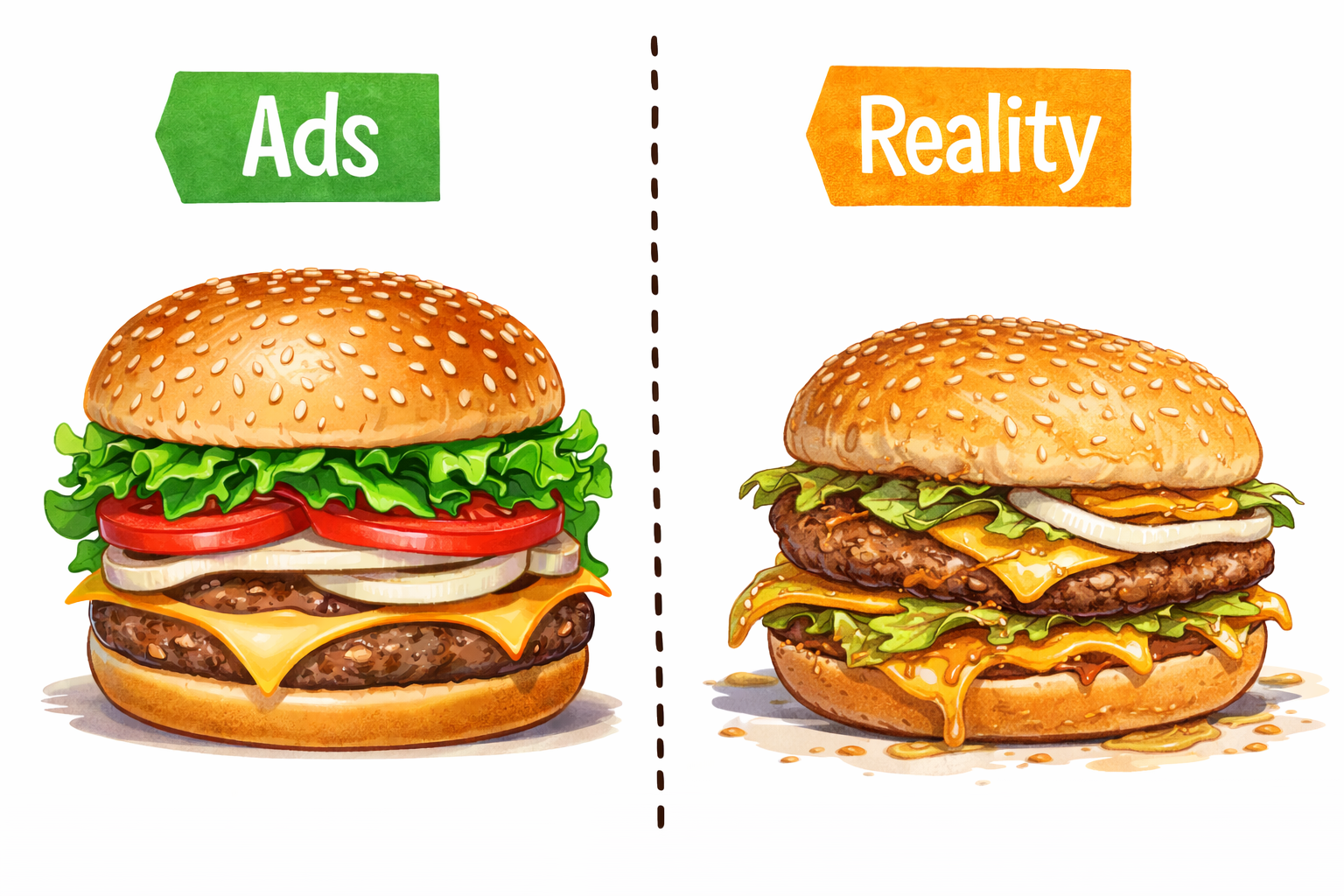

Misleading and deceptive conduct occurs when a business’s marketing creates a false impression that could cause consumers to make a decision they would not otherwise make (e.g., buying, paying more, signing up, travelling to a store).

This dotpoint focuses on three areas where marketing can mislead consumers if not managed ethically:

- Bait advertising

- Scientific claims

- Country-of-origin representations

⚖️What counts as “misleading” in marketing?

The simple test

- What does the ad make an ordinary customer think?

- If that overall impression is wrong → it can be misleading, even if each sentence looks “technically true”.

In Australian Consumer Law, the key idea is: marketing must not mislead or deceive (or be likely to). Intent is not the main issue — the effect on consumers is.

Exam-friendly wording

Misleading and deceptive conduct occurs when a business’s marketing creates a false impression that could cause consumers to make a decision they would not otherwise make (e.g., buying, paying more, signing up, travelling to a store).

Two ways businesses get in trouble

- Misleading conduct: the overall behaviour / advertising creates the wrong impression.

- False or misleading claims: specific statements or representations are not true (or are half-truths).

Where it happens

- Online ads, websites, social media posts, influencer promotions

- Price tags, catalogues, “was/now” discounts, email marketing

- Packaging labels (health claims, “Australian made”, “eco-friendly”)

- Sales calls, in-store claims, fine print, subscription sign-ups

- Clear pricing and conditions (no hidden “gotchas”).

- Claims can be proven (evidence exists).

- Disclaimers match the headline and are easy to see.

- Customers can make an informed choice.

- Big headline claim + tiny conditions that change the meaning.

- “Limited time” or “limited stock” used when it isn’t true.

- Scientific words used to sound credible without real proof.

- Origin claims that are vague or create the wrong impression.

🎣Bait advertising

Bait advertising is when a business advertises a product at a very attractive price to bring customers in, but the product is not actually available in reasonable quantities (or for a reasonable time).

What makes it illegal?

- The business promotes a “deal” to attract customers…

- …but has no reasonable supply (or no plan to supply) at that price.

- Customers waste time travelling, lining up, or changing plans because of the ad.

This is especially common in catalogue specials, flash sales, and limited-time online drops.

- Stock enough units for the expected demand.

- If supply is limited, say so clearly (upfront).

- Offer a raincheck or a reasonable substitute where appropriate.

- Train staff to handle “sold out” fairly and consistently.

- Very low stock + big advertising spend.

- “While stocks last” hidden in tiny print while headline screams the deal.

- Steering customers to a higher-priced item immediately (“upsell”).

- Online “from $X” deals where almost nobody can actually buy at $X.

WA example

A Perth electronics store advertises “Today only: Air Fryer $49” across social media. If only a handful exist and the store knew demand would be far higher, customers could argue the promotion created a false impression of availability.

Legal vs illegal

- Legal: The deal is real, the business has reasonable stock (or clearly states limits upfront), and it offers fair solutions when stock runs out.

- Illegal: The low-price deal is used as bait when there is no reasonable supply, creating a false impression customers can realistically buy it.

Consequences: complaints to the ACCC/consumer regulators, forced changes to advertising, refunds or corrective action, reputational damage, and in serious cases large financial penalties.

🧪Scientific claims

Scientific claims are statements that rely on science to persuade customers — e.g., “clinically proven”, “kills 99.9%”, “boosts immunity”, “backed by research”, “lab tested”, “reduces anxiety”, “burns fat”.

Why this is risky in marketing

- Scientific language increases trust — so customers are more likely to buy.

- If the claim can’t be backed up with solid evidence, it can create a false impression.

- Even true information can be misleading if it is presented out of context (e.g., cherry-picking one small study).

Extra layer for health products: If the claim relates to medicines, supplements, or medical-style outcomes, the business may also fall under the Therapeutic Goods Act and the rules around advertising therapeutic goods. That means health claims need even stronger evidence and must be presented in a way that does not mislead the public.

- Claims match the overall body of evidence, not one “hand-picked” result.

- Language is clear for normal consumers (not designed to confuse).

- Studies are identifiable and accessible (where relevant).

- Before-and-after results are typical, not “best case only”.

- Vague claims: “Scientifically proven” with no explanation.

- Big health promise + no reliable testing.

- Using a “doctor” image or lab coat to imply approval.

- Statistics used in a way that changes the meaning (e.g., absolute vs relative).

WA example

A Perth supplement brand claims its product “reduces stress by 60%”. If there is no strong, relevant evidence (or the claim is based on a tiny/irrelevant study), the marketing could mislead customers into believing the product will deliver a reliable medical outcome.

Legal vs illegal

- Legal: The business can prove the claim with solid evidence and presents it clearly (no cherry-picking or confusing statistics).

- Illegal: The claim can’t be substantiated, is exaggerated, or uses “science words” to create a false impression.

Consequences: advertising must be changed or removed, consumer backlash, refunds or corrective statements, and enforcement action. If the claims are health/medical related, penalties can be more serious because the Therapeutic Goods Act may also apply.

🌏Country of origin

Country of origin claims tell customers where a product is made, grown, or produced. Origin matters because it influences trust, quality perceptions, and willingness to pay (e.g., “Made in Australia”).

What can be misleading?

- Using Australian symbols/flags that create an “Australian made” impression when it’s not.

- Wording that is technically true but still misleading (e.g., “Australian owned” ≠ “Made in Australia”).

- Big origin claim on the front + correction hidden on the back.

The key idea

Origin claims must be clear, truthful and accurate. If the overall impression suggests “Australian made”, the business needs to ensure the claim matches reality — otherwise it can mislead consumers and competitors.

WA example

A Perth skincare brand uses big “Australian” branding on the label, but the product is manufactured overseas and only packaged locally. If customers are led to believe it is “made in Australia”, that overall impression can be misleading.

Legal vs illegal

- Legal: Origin wording is accurate and clear (e.g., “Made in…”, “Product of…”, “Packed in…”) and the packaging doesn’t create a false impression.

- Illegal: The branding/label creates an “Australian made” impression when it’s not true, or key clarifications are hidden in fine print.

Consequences: forced label changes, product relabelling costs, refunds/returns pressure, loss of trust, and in serious cases large penalties. Competitors can also complain if origin claims create unfair advantage.

📊Table Summary of the Three

| Area | What it means | What becomes misleading | How a business stays safe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bait advertising | Using a standout low price to attract customers. |

|

|

| Scientific claims | Using science/medical-style evidence to persuade customers. |

|

|

| Country of origin | Claims about where goods are made/grown/produced. |

|

|

🧾Other examples of misleading or deceptive conduct

- Fine print tricks: important conditions hidden or unclear (e.g., extra fees, short contract length, auto-renew).

- Hidden/extra pricing: showing a low price upfront but adding unavoidable charges later (delivery, booking, “service fees”).

- Prizes & gifts not honoured: “Win a free ____” promotions where the prize is not realistically available or conditions aren’t clear.

- Puffery: exaggerated claims that are clearly opinion (often not illegal) — e.g., “Best coffee in the world”.

Mini rule for students

If the statement is likely to influence a customer’s decision and it sounds like a real promise (not just hype), the business should be able to prove it.

🇦🇺Real Australian case study

Case study: Nurofen — The brand promoted different products as being designed for specific types of pain (e.g., “targeted” pain relief), even though the products were essentially the same medicine and worked the same way.

What the marketing implied

- Customers were led to believe certain products were better for certain pains.

- The packaging and wording created a strong “targeted” impression.

- That impression influenced purchasing (customers paid more for the “right” one).

- The overall impression suggested a real difference in how each product worked.

- Customers were making decisions based on that impression.

- The business could not justify the implied performance difference.

- Packaging/claims had to be changed to stop the false impression.

- The business faced serious penalties and reputational damage.

- Customers became more sceptical of “science-sounding” marketing.

🎧 Prefer listening?

If you prefer listening to the content in Podcast format:

🎥 Prefer watching?

If you prefer watching the content in video format:

Biz Fact: Harvey Norman was penalised $1.25 million by the Federal Court after its promotional catalogue created a misleading impression about the availability and functionality of products like 3D TVs.